How Economics Dictates Strategy

This is the first part of a two-part series exploring how economics shapes strategy. In Part 2, we will explore the competitive moats and strategic positioning of companies like Tesla, Zoom, and Campbell Soup.

Why Strategy is Shaped by the Realities of Economics

Why does Tesla obsess over gigafactories? How does Zoom scale to millions of users while keeping costs low? And why can’t Campbell Soup endlessly cut costs by producing more cans?

The answer lies in a universal truth: economics drives strategy.

Put another way, strategy is not an abstract vision — it’s the set of tangible options left once the economics of a situation are understood.

Take any successful company, and you’ll find its strategic decisions shaped by three fundamental concepts:

- Fixed and Variable Costs: How the balance between these determines scalability.

- Economies of Scale: Why spreading fixed costs across greater production unlocks competitive advantages.

- Diminishing Returns: The point where scaling further ceases to provide meaningful cost savings.

Whether it’s Tesla’s scaling of EV production, Zoom’s focus on user acquisition, or Campbell Soup’s battle with logistical costs, these principles reveal not just why companies act the way they do, but also how they gain or lose their edge. Understanding these principles allows us to anticipate a company’s moves and uncover its greatest challenges. To borrow a chess analogy: once you understand the current position and constraints, there are only a handful of possible moves left.

From these first principles, we can derive how strategy takes shape — why some companies are compelled to scale aggressively, others must pivot, and why even the boldest ambitions encounter inevitable constraints.

The Foundations of Economics in Strategy

Economics determines not just a company’s starting point but also its trajectory. By examining fixed and variable costs, economies of scale, and diminishing returns across industries, we see how these principles act as both enablers and constraints.

1. Fixed and Variable Costs: The Bedrock of Scalability

Fixed costs — whether it’s Tesla’s $5B Gigafactories, Zoom’s infrastructure investments, or Campbell Soup’s production facilities — create high barriers to entry but also set the stage for potential cost advantages. These investments often define a company’s ability to scale efficiently.

Variable costs, like Tesla’s raw materials or Campbell’s logistics and labour expenses, grow with each unit produced. The ratio between fixed and variable costs determines scalability: the higher the proportion of fixed costs, the more a company benefits from economies of scale.

2. Economies of Scale: Turning Costs into Advantages

Scaling spreads fixed costs over more units, reducing cost per unit and creating room for competitive pricing.

For Tesla, producing millions of cars amortises the immense cost of its factories. For Zoom, each new user adds minimal cost, as the same servers host additional calls. In both cases, scaling transforms costs into advantages.

3. Diminishing Returns: The Growth Ceiling

However, the benefits of scaling are not infinite. Eventually, variable costs dominate, and operational complexities add friction. Campbell’s production flattens early due to logistical constraints, while Tesla hits physical limits at higher volumes. Zoom, too, faces diminishing returns as it saturates its market, with each incremental user adding less marginal value.

Strategic Implications of Economic Principles

Every strategic decision stems from a company’s economic realities. The interplay of fixed and variable costs, economies of scale, and diminishing returns shapes how companies grow, compete, and pivot.

Zoom: Scaling for Digital Dominance

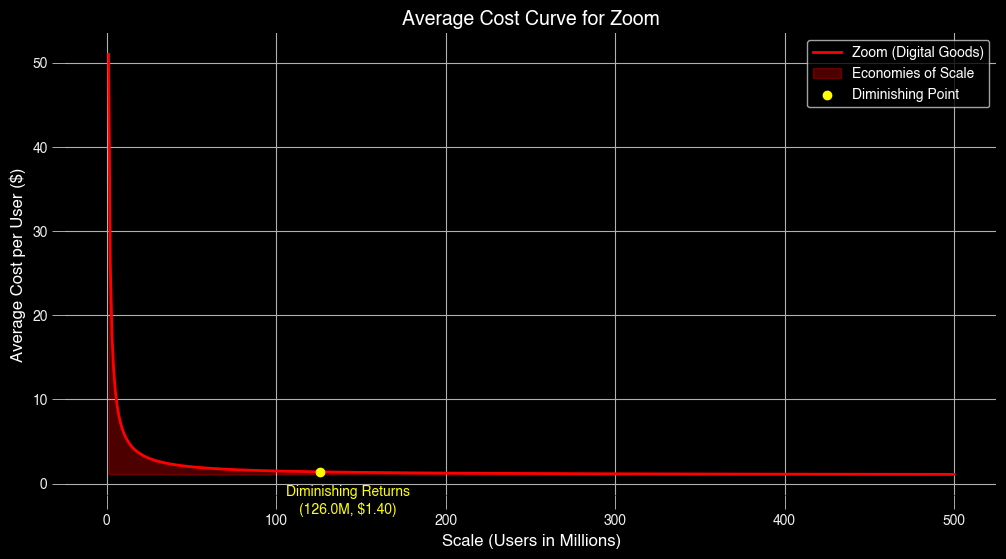

Zoom’s business model exemplifies economies of scale: infrastructure investments are spread across a growing user base, while minimal variable costs (e.g., server bandwidth per user) enable rapid reductions in average costs as the platform scales. Strategies such as free-tier offerings attract users, while enterprise upselling maximises returns.

However, as diminishing returns emerge beyond approximately 120M users, scaling further yields negligible cost advantages. At this stage, Zoom’s focus must shift to maximising customer lifetime value through premium services, customer retention, and advanced features such as AI-driven tools.

This pivot highlights the delicate balance digital companies face between scaling aggressively and maintaining quality.

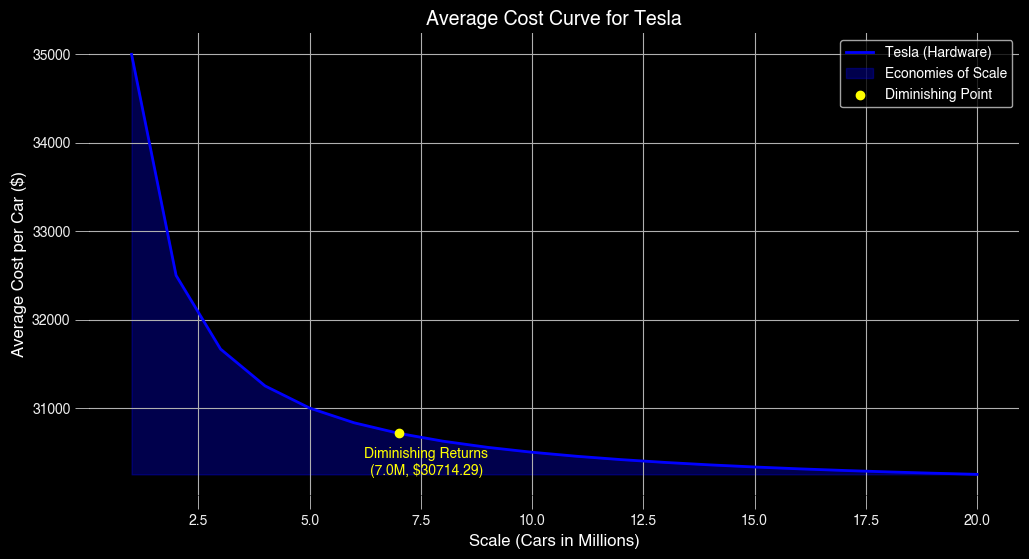

Tesla: Scaling Hardware Profitably

Tesla’s strategy is built on leveraging economies of scale. By producing millions of cars annually, Tesla spreads fixed costs—like those of its Gigafactories—across a vast output, reducing average costs per vehicle and supporting competitive pricing in the EV market.

Yet, diminishing returns beyond about 7M cars reveal the physical limits of manufacturing and supply chain constraints. Tesla counters this by vertically integrating operations (e.g., securing battery material supplies) and diversifying into adjacent markets, such as energy storage and autonomous technology.

This balancing act between scaling and innovation is central to Tesla’s long-term growth.

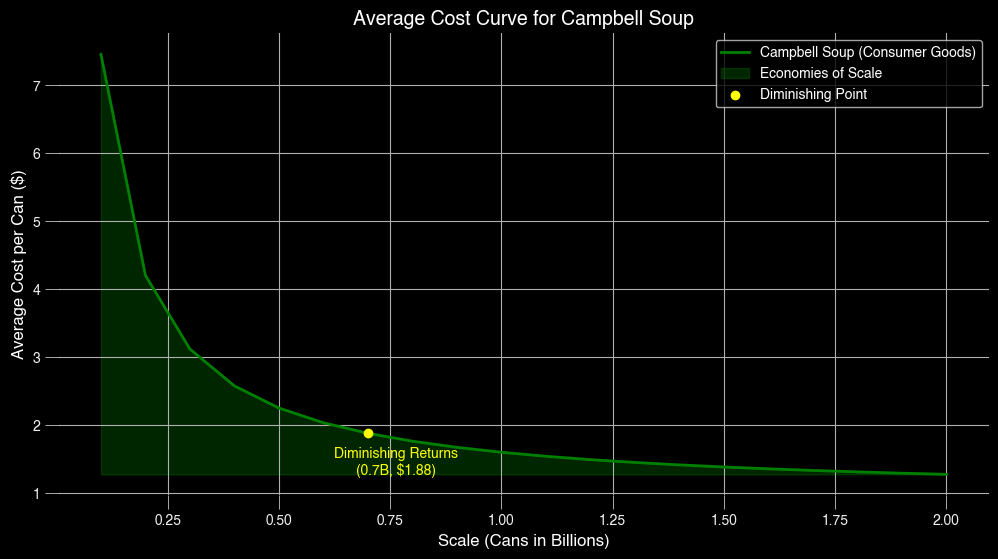

Campbell Soup: Battling Flat Margins

Campbell Soup’s high fixed costs — manufacturing facilities and logistics — enable some economies of scale, but significant variable costs tied to raw materials, transport, and labour limit its ability to achieve the dramatic cost reductions seen in digital or hardware businesses.

Diminishing returns emerge beyond approximately 600M cans annually, reflecting these structural constraints. To navigate this, Campbell must prioritise pricing power via branding, and product differentiation. Strategies such as leveraging brand loyalty, launching health-focused products, and expanding into high-growth snacking categories are pivotal to sustaining margins in a competitive market.

A Note about the Graphs

The graphs in this article represent estimated data based on open-source and publicly available information. While I have made every effort to ensure reasonable accuracy, these figures should be interpreted as illustrative rather than definitive.

Conclusion: Economics as the Compass for Strategy

Economics doesn’t just inform strategy—it defines its boundaries. The interplay between fixed and variable costs, economies of scale, and diminishing returns reveals why companies act as they do and sheds light on the constraints they face.

Zoom demonstrates how economies of scale power growth in digital businesses, where rapid scaling drives cost efficiencies—but only up to a point. Tesla shows the importance of balancing aggressive scaling with innovation, as it juggles physical limits in production with new opportunities in adjacent markets. Meanwhile, Campbell Soup underscores the limits of scale in consumer goods, where competitive advantages often hinge on brand strength and pricing power rather than production volume.

But this is just one side of the story. Economic structures provide the foundation, yet it’s a company’s competitive moat—the thing that keeps others from eating into its profits—that determines whether it can sustain these advantages. How do these companies defend their positions? Where are they vulnerable? And what risks and opportunities lie ahead?

A Preview of What’s Next

In the next piece, I’ll go beyond the economics to analyse these businesses through the lens of competitive advantage and strategic positioning.

By exploring the moats that protect them and the forces shaping their industries, we’ll understand not just where they stand today but what the future might hold — for the companies and their investors.

Key Takeaways

- Zoom: Scale aggressively to approximately 120M users, then pivot to profitability through upselling and retention.

- Tesla: Sustain competitive pricing through scaling to approximately 7M cars annually while investing in vertical integration and diversification.

- Campbell: Focus on brand strength and innovation rather than pure volume to drive margins in a constrained market.

Member discussion